Biomimicry in Architecture

Biomimicry is the use by man of designs in nature. Nature has solved most of the problems we face. We are simply copying a successful design solution and applying it elsewhere.

When the Wright brothers studied pigeons to develop their concepts for manned flight they were engaging in biomimicry.

In architecture biomimicry has been used from early on to develop building materials, techniques, proportions and decoration.

It is speculative, but the mixing of straw with clay to produce bricks may simply been an imitation of the strong bond that grass roots form with the ground. The use of sod to form walls was simply using natural materials, but the use of straw in clay to imitate this bond would have been an early act of biomimicry.

The use of columns to support a temple roof probably originated with the use of tree trunks to support a roof. When temples transitioned to stone the natural form was maintained down to the thinning of the column at its upper reaches. The spreading of branches was replicated in the capital that crowned the column.

Both of these examples are sort of a secondary mimicry. You use the natural product and then you copy the natural product, but you are not borrowing from nature directly. In nature the trees don’t support heavy roofs and sod does not stack itself into walls.

A primary imitation of nature in architecture involves looking at nature directly to see how natural forms can be applied to the act of building. An example would be the column arches at the Sagrada Familia cathedral designed by Antoni Gaudi. This unique combination of columns that branch out into arches imitates trees, but they also imitate the natural form of the catenary arch. The columns do not meet the ground perpendicular, but come in at a reduced angle, so that the columns on either side of the aisle imitate the curve of a catenary arch. Gaudi developed this structure by examining natural forms.

In other buildings Gaudi used columns that imitated the shapes of bones. Animal bones support weight so he knew it was a form that could be used for this purpose. The thinning of the bones on the end meant that the bone is thickest where it is most subject to bending stresses.

The modern age provided an interruption in the way we look to nature for solutions to problems. The industrial revolution brought us steel and plate glass and the return of reinforced concrete and a reliance on motive power, all of which, for a time, distorted how we looked at designing things, at least in the realm of architecture.

Architects looked at the new materials and envisioned new structures entirely segregated from past forms. Nature seemed to be a look back rather than a look forward.

With steel beams great open areas could be spanned without resorting to arches. With the strength that was possible from such a structure buildings could be skinned in glass. The resulting buildings, especially those in the International style, were often large boxes devoid of any reference to nature. There was no biophilic connection, and no biomimetic connection. Man had conquered nature and cast her aside.

This is a simplification. There were always some who looked to nature, but I think it is an accurate simplification.

Even in decoration the modernists forgot nature. They eliminated it entirely, relying on the shape, line and mass of the structure itself.

Previously much of our architectural decoration was directly dependent upon natural forms. Corinthian capitals were patterned after Acanthus leaves. The volutes often used as decoration were taken from curved horns, or fronds, or the other places where nature has repeated this pattern. The Rococo style brought us the exuberant use of seashells and various sinuous forms. Fish scales, leaves, fruit, grain all found their way to the surfaces of walls and moldings. The Bible records the use of pomegranates on the capitals atop the columns in front of Solomon’s Temple.

Even geometric forms can be found in nature. There is such a range in nature’s design that it can be difficult to avoid copying it.

There can even be a bias towards favoring biomimetic art. Part of what determines how we like something is how comfortable we are with it, and that is often determined by prior exposure. To some degree we are all exposed to nature, even if it is only nature in the form of other people. This bias toward the natural gives us a predisposition to favor designs that we have seen in nature.

While modernism isn’t exactly dead, there has been a move away from its sterility and part of that reaction has been a renewed interest in what nature can teach us about design. Whether this design is graphical or mechanical nature is finding its way back into buildings.

An example of borrowing from nature to enhance a building's mechanical system is the ventilation system that architect Mick Pierce designed for Eastgate Centre in Zimbabwe. Eastgate Centre is a modern office and retail complex. On the surface it looks like many other buildings. It is in the innards where Mick Pierce showed he was paying attention to what nature could teach.

Eastgate Centre is the wide building with the red roof and the multiple chimneys. Those chimneys are critical to Mick Pierce's imitation of the termite's cooling system. Photo courtesy David Brazier via Wikimedia Commons.

Zimbabwe is a tropical country, although at an altitude of around 4500 feet the daytime temperature in Harare tends to stay in the seventies to low eighties, while it drops down to the forties and fifties at night (in Fahrenheit, in Celsius it stays in the twenties during the day). Daytime swings between high and low temperatures average about 14 degrees Celsius.

The other modern buildings rely on overpowering nature with lots of air conditioning. Eastgate uses a cooling system borrowed from the termites of the Zimbabwe Savannah. They form large termite mound, in some ways very similar to office buildings, in a climate very close to that of Harare’s, yet the keep the internal temperature regulated within 1 degree Celsius.

In dryer climates termites keep the temperature constant by digging deep and living underground. Zimbabwe’s wet climate would result in a lot of drowned termites if they followed this strategy. Instead they build up, but this leaves their mounds exposed to the sun. To keep their mounds cool they are adept at catching the lightest breezes, which are funneled into the moist soil below the mound. The cooled air is then vented through their living areas. Cold air at night is warmed by the soil before it enters the living area while it also chills the ground. The termites regulate the temperature by opening and closing vent channels.

Eastgate has a similar structure. While it augments natural ventilation with fans to move the air, like the termite mounds it uses the cool night air to chill the hollow floors. Large fans provide a change of air seven times an hour. During the day smaller fans pull air from the atrium at a rate of two times an hour. The air exchange schedule varies by season and accommodates the different exterior conditions, much as the termites do by controlling the ventilation in their mounds.

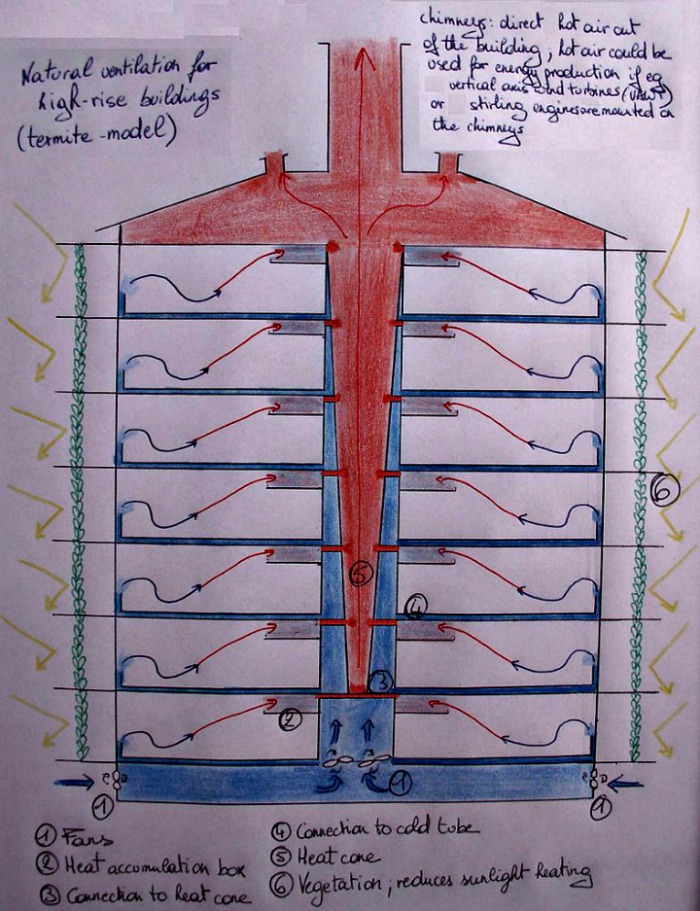

Sketch by KVDP at Wikimedia. This is a cross section of the Eastgate Centre showing a the ventilation scheme for the building.

The building is masonry, which provides a thermal mass, much as the termites use the thermal mass of the dirt to regulate temperatures. It also is careful to avoid heat gain by ensuring that windows are indented back from the surface of the building, never receiving the direct rays of the mid-day sun. Termite mounds lack windows, but termites have a similar strategy. They orient their mounds to present only a thin face to the sun when it is at its peak.

Like the termites, Mick Pearce uses the height of the structure to create a chimney effect, enhancing the ventilation efficiency.

40% of the world’s energy goes to heating and cooling buildings, so the gains we could achieve with this type of structure could have a significant impact on our global economy and environment.

Which leads back to the point of biomimicry. Solutions already exist to many of the challenges we face. Nature is naturally efficient in most of her processes and her solutions are usually better than ours. We have a master teacher in nature, now we just need to learn to be good pupils.

To Top of Page - Biomimicry

Home - House Design

Please!

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.